# Relationships in Mongo: Referenced Data

Relationships in Mongo: Referenced Data

| Objectives |

|---|

| Describe one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many data relationships. |

| Write mongoose schemas for Mongoose's "reference" pattern of relating data. |

Build the appropriate queries for referenced data relationships using populate(). |

| Incorporate referenced data handling into express server routes. |

Real-world data usually consists of different types of things that are related to each other in some way. A banking app might need to track employees, customers, and accounts. A food ordering app needs to know about restaurants, menus, and its users! We've seen that when data is very simple, we can combine it all into one model. When data is more complex or less closely tied together, we often create two or more related models.

Today we'll look at ways to think about relationships between two data records. The first is a brief foray into cardinality - how many of each type of thing participate in the relationship?

The second deals with where data is stored.

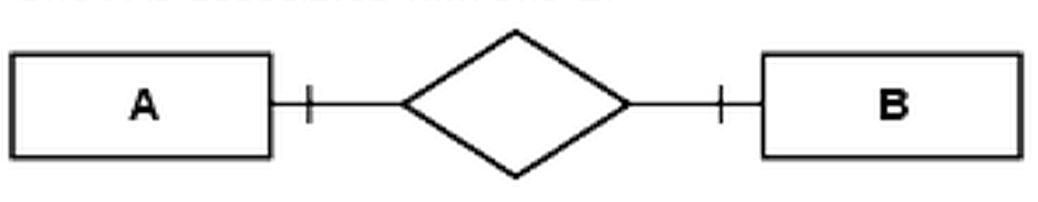

Each person has one brain, and each (living human) brain belongs to one person.

One-to-one relationships can sometimes just be modeled with simple attributes. A person and a brain are both complex enough that we might want to have their data in different models, with lots of different attributes on each.

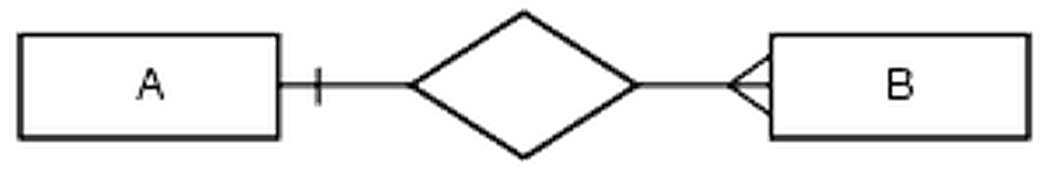

Each youtube creator has many videos, and each video was posted by one youtube creator.

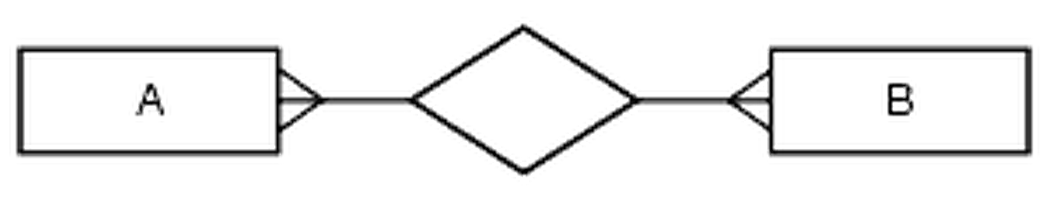

Each student can go to many classes, and each class has many students.

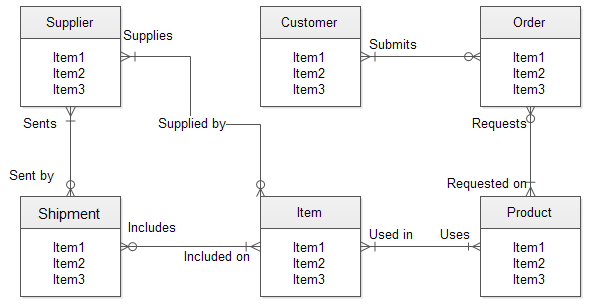

Entity relationship diagrams (ERDs) represent the relationships between data or entities.

Note: Attributes can be represented as line items under a heading (like all of the Item1, Item2, Item3 under each heading above) or as ovals stemming from the heading's rectangle.

While cardinality is often determined by real-world characteristics of a relationship, the decision to embed or reference data is a design decision.

Embedded Data is directly nested inside of other data. Each record has a copy of the data.

Referenced Data is stored as an id inside other data. The id can be used to look up the information. All records that reference the same data look up the same copy.

There are tradeoffs of efficiency and consistency depending on which one you choose.

It's often more efficient to embed data because you don't have to make a separate request or a separate database query -- the first request or query gets you all the information you need.

It's easier to stay consistent when you reference data because you only keep one copy around. You don't have to worry that you'll forget to update or delete one copy of the data.

How would you design the following?

- A

Userthat has manyTweets? - A

Foodthat has manyIngredients?

// pull in mongoose module with require

var mongoose = require('mongoose');The above code is the standard boilerplate mongoose setup that you will see in any seed.js or Model file.

This next snippet only needs to happen once in your server-side code or models. It will usually be in your main server code (server.js) or in your models index (/models/index.js) if you have one.

// connect to the mongoose `test` database on this computer

mongoose.connect('mongodb://localhost/test');When we actually want to set up MongoDB data, we start with the Schema.

Here's a reminder of the major SchemaTypes MongoDB can store:

- String

- Number

- Date

- Buffer

- Boolean

- Mixed

- ObjectId <- used to create referenced data relationships!

- Array

// giving mongoose.Schema a shorter name for convenience

var Schema = mongoose.Schema;

// set up the videogame platform schema

/* Platform Schema */

var platformSchema = new Schema({

name: String,

manufacturer: String,

released: Date

});The platformSchema describes a videogame platform such as Nintendo, Sega, or XBox.

/* Game Schema */

var gameSchema = new Schema({

name: String,

developer: String,

released: Date,

// I'm telling platforms to EXPECT references to Platform documents

platforms: [

{

type: Schema.Types.ObjectId,

ref: 'Platform'

}

]

});The Game Schema above describes an actual videogame such as Super Mario Bros., MegaMan, Final Fantasy, and Skyrim.

Note the specific code starting on line 7 within the [] brackets. With the brackets, we're letting the Game Schema know that each game will have an array called platforms in it. Inside the [], we're describing what kind of elements will go inside a game's platforms array as we work with the database. In this case we are telling the Game Schema that we will be filling the platforms array with ObjectIds, which is the type of that big beautiful _id that Mongo automatically generates for us.

If you forgot, it looks like this: 55e4ce4ae83df339ba2478c6. That's what's going on with type: Schema.Types.Objectid.

When we have the code ref: 'Platform', that means that we will be storing ONLY ObjectIds associated with the Platform document type. Basically, we will only be putting Platform ObjectIds inside the platforms array -- not the whole platform object, and not any other kind of data object.

Now that we have our schemas defined, let's compile them all into active models so we can start creating documents!

/* Compiling models from the above schemas */

var Game = mongoose.model('Game', gameSchema);

var Platform = mongoose.model('Platform', platformSchema);Let's make two objects to test out creating a Console document and Game document.

/* make a new Platform document */

var nin64 = new Platform ({

name: 'Nintendo 64',

manufacturer: 'Nintendo',

released: 'September 29, 1996'

});/* make a new Game document */

var zelda = new Game ({

name: 'The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time',

developer: 'Nintendo',

release: new Date('April 27, 2000'),

consoles: []

});Notice that we start the platform array empty within our zelda game document. That will be filled with ObjectIds later on.

Now we'll save our work.

nin64.save(function(err, nintendo64) {

if (err) {

return console.log(err);

} else {

console.log('nintendo 64 saved successfully');

}

});

zelda.platforms.push(nin64);

zelda.save(function(err, zeldaGame) {

if (err) {

return console.log(err);

} else {

console.log('zelda game is ', zeldaGame);

}

});Note that we push the nin64 platform document into the zelda platforms array. Since we already told the Game Schema that we will only be storing ObjectIds instead of actual Platform documents in the platforms array, mongoose will convert nin64 to it's unique _id and save that for us!

This is the log text after executing the code we've written thus far:

zelda game is { __v: 0,

name: 'The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time',

developer: 'Nintendo',

_id: 55e4eb857d6157f4d41a2981,

platforms: [ 55e4eb857d6157f4d41a2980 ] }

nintendo 64 saved successfully

What are we looking at?

-

Line 1:

__vrepresents the number of times the document has been accessed. -

Line 2: The name property of the Game Document we have created.

-

Line 3: The developer property of the Game Document we have created.

-

Line 4: The unique

_idcreated by Mongoose for our Game Document. -

Line 5: The platforms array, with a single

ObjectIdthat is associated with our Platform Document.

Let's print out the Platform Document nintendo64 to make sure the ObjectId in platforms matches the _id we see for this game:

Platform.findOne({_id: "55e4eb857d6157f4d41a2980"}, function (err, foundPlatform) {

if (err) {

return console.log(err);

}

console.log('found platform: ', foundPlatform);

});found platform: { _id: 55e4eb857d6157f4d41a2980,

name: 'Nintendo 64',

manufacturer: 'Nintendo',

released: Sun Sep 29 1996 00:00:00 GMT-0700 (PDT),

__v: 0 }

Sure enough, the only ObjectId from the game's platforms array matches the Platform Document _id we created!. What's going on? The Game Document platforms has a single Objectid that contains the 'address' or the 'location' where it can find the Platform Document if and when it needs it. This keeps our Game Document small, since it doesn't have to have so much information packed into it. When we need the Platform Document data, we have to ask for it explicitly. Until then, mongoose is happy to show just the ObjectId associated with each platform in the game's platforms array.

When we want to get full information from a Platform Document we have inside the Game Document platforms array, we use the method call .populate().

Game.findOne({ name: 'The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time' })

.populate('platforms')

.exec(function(err, game) {

if (err){

return console.log(err);

}

if (game.platforms.length > 0) {

for (var i=0; i<game.platforms.length; i++) {

console.log("/nI love " + game.name + " for the " + game.platforms[0].name);

}

}

else {

console.log('Game has no platforms.');

}

console.log('what was that game?', game);

});Let's go over this method call line by line:

-

Line 1: We call a method to find only one Game Document that matches the name:

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. -

Line 2: We ask the platforms array within that Game Document to fetch the actual Platform Document instead of the

ObjectIdreferencing that Platform Document. -

Line 3: When we use

findwithout a callback, thenpopulate, like here, we can put a callback inside an.exec()method call. Technically we have made a query withfind, but only executed it when we call.exec(). -

Lines 4-15: If we have any errors, we will log them. Otherwise, we can display the entire Game Document including the populated platforms array.

-

Lines 9 and 15 demonstrate that we are able to access both data from the original Game Document we found and the referenced Platform Document we summoned.

What is the actual game output from the above `findOne()` method call with `populate`?

{ _id: 55e4eb857d6157f4d41a2981,

name: 'The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time',

developer: 'Nintendo',

__v: 1,

platforms:

[ { _id: 55e4eb857d6157f4d41a2980,

name: 'Nintendo 64',

manufacturer: 'Nintendo',

released: Sun Sep 29 1996 00:00:00 GMT-0700 (PDT),

__v: 0 }

]

}

I love The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time on the Nintendo 64

Now, instead of seeing only the ObjectId that pointed us to the Platform document, we can see the entire Platform document. Notice that the Platform document's _id is exactly the same as the ObjectId that was previously referencing it. They are one in the same!

Remember to always make "RESTful" routes. RESTful routes are the most popular modern convention for designing resource paths for nested data. Here is an example of an application that has routes for Store and Item models:

RESTful Routing

| HTTP Verb | Path | Description |

|---|---|---|

| GET | /api/stores | Get all stores |

| POST | /api/stores | Create a store |

| GET | /api/stores/:id | Get a store |

| DELETE | /api/stores/:id | Delete a store |

| GET | /api/stores/:store_id/items | Get all items from a store |

| POST | /api/stores/:store_id/items | Create an item for a store |

| GET | /api/stores/:store_id/items/:item_id | Get an item from a store |

| DELETE | /api/stores/:store_id/items/:item_id | Delete an item from a store |

In routes, avoid nesting resources deeper than shown above.

Most of your routes for creating each piece of data will be the same, since games and consoles can exist independently of one another. However, when getting information about a game, remember to pull console data in with populate. Here are a few examples:

// send all information for a single game

app.get('/api/games/:gameId/', function (req, res) {

Game.findOne({ _id: req.params.gameId })

.populate('platforms')

.exec(function(err, game) {

if (err) {

res.status(500).send(err);

return;

}

console.log('found and populated game: ', game);

res.json(game);

});

});// send all information for all games

app.get('/api/games/', function (req, res) {

Game.find({ })

.populate('platforms')

.exec(function(err, games) {

if (err) {

res.status(500).send(err);

return;

}

console.log('found and populated all games: ', games);

res.json(games);

});

});But would we always want to populate all the game information before sending it back? Many APIs don't. For instance, the Spotify API is riddled with ids that developers can use to make a second request if they want more of the information.

// create a game, given the name of a console it can run on

app.post('/api/games/', function (req, res) {

var newGame = new Game({

name: req.body.title,

developer: req.body.developer,

release: new Date(req.body.releaseDate),

platforms: []

});

Platforms.findOne({ name: req.body.platform }, function (err, foundPlatform) {

if (err) {

res.status(500).send(err);

return console.log(err);

} else if (foundPlatform){

newGame.platforms.push(foundPlatform);

} else {

console.log('platform not found: ' + req.body.platform + ' - leaving platforms array empty');

}

newGame.save(function (err, savedGame){

if (err) {

res.status(500).send(err);

return console.log(err);

}

res.send(newGame);

});

});

});Sprint 2 of Mongoose Books app